When Steven Ochs and Gerald Taylor won the contract to create a mural for the entryway of the Freeman Justice Center, the new Monroe County courthouse in Key West, Fla., the Arkansas artists were expected to capture the essence of the building’s namesake in concrete.

The Freeman family is one of the most respected in Florida Keys history. From 1924 to 2000, six family members amassed 106 years of public service in a variety of elected offices, all without a blemish on their records.

Ochs and Taylor traveled to Key West and met with Dr. Shirley Freeman, former mayor of Key West and ex-county commissioner, to help them understand the legacy of her late husband, Billy Freeman Jr., who served for 34 years as a county commissioner, a Florida state representative and the local sheriff. At first, the sidewalk mural was going to focus on Billy Jr. alone.

However, Shirley eventually decided it would be better to highlight the accomplishments of all six Freeman public servants.

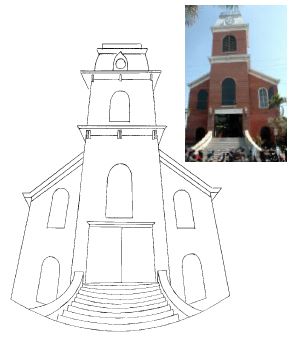

Each of her relatives had saved a historic building in some way. From a modest dwelling for railroad workers on Pigeon Key to an old electricity plant transformed into modern-day Key West condos to the gingerbread-style Freeman family home where Shirley still lived, the buildings represented the eras in which each Freeman had served.

For the next three days, Ochs and Taylor found and photographed the buildings while tooling around on one-of-a-kind bicycles hand-painted by the appropriately named Captain Outrageous.

The bikes – supplied by their island hostess, The Gallery on Greene owner Nance Frank – not only allowed them to blend with the natives, Ochs says, but “offered a means to conduct research at a pace that was easier to process.”

Next came the hard part. Ochs, an art professor at Southern Arkansas University in Magnolia and owner of Public Art Walks, and Taylor, owner of Images in Concrete, a decorative concrete outfit based in El Dorado, Ark., returned home to tackle the most challenging phase of the project – creating a design that incorporated depictions of all six buildings and made structures ranging in style from art deco to Greek revival look like they belonged together.

“(To unify the image) we came up with a circular format and a one-point perspective with exaggerated ellipses,” Ochs says. “Distorting each building with linear and elliptical perspectives while retaining their identities was my attempt to pull it all together.”

Once Shirley Freeman whittled seven proposals down to one, Ochs and Taylor made a template. “By tracing a line image projected onto a sheet of plastic, we created a pattern, and then we burned tiny holes along the lines so a chalk-filled pounce bag could transfer the image once we returned to site,” Ochs says. With design in hand, they were ready to head back to the Keys in mid-August 2008 – not realizing it was also prime hurricane season.

At work in the Keys

When the artful duo returned to Key West, they learned they had only three days before Tropical Storm Fay was scheduled to make landfall. With no time to waste, they positioned the pattern and transferred the image.

“Gerald scored the curved lines with the aid of a diamond-blade angle grinder attached to a compass beam and freehand-cut many of the straight lines,” Ochs says.

They then cleaned and etched the slab with Green Clean from Smith Paint Products. Although they had been using a Smith cleaner for nearly five years – they usually used CT-8 cleaner – this was the first time for Green Clean, an organic acid that reminded Ochs of hair gel.

He liked it because it was easy to use. “It would stay exactly where we put it and only required some light broom action to spread it around equally.” He also didn’t have to worry about the gel absorbing or drying too quickly before the etching was complete.

“Usually we have to scrub with a floor machine or add water and frantically agitate with brushes,” he says. “You could tell immediately by the rate of foaming that this product worked aggressively, and it was a welcomed break to sit back for 20 minutes while we watched it boil.”

After rinsing, they applied a base coat of Smith Color Floor, a water-based concrete stain, with Smith Base Boost, a blend of silicates that promotes substrate adhesion. “When mixed with the stain, Base Boost improves its adhesion by chemically reacting with the unhydrated calcium hydroxide particles in the concrete to lock (the stain) into the substrate,” Ochs explains. “This reduces the dusting or fines typical with new concrete.”

Not too bad for a day’s work. After a few hours sleep, for the next 25 hours Ochs and Taylor endured the knee-numbing, sun-blistering task of painting the details.

Day two

Turns out, the August sun in Key West is brutal. “I had never seen anybody get sunburned through their shirt before,” Ochs says about Taylor. “Ironically, it was lobster season in the Keys.”

Later that afternoon, a member of the Arts Council put up a tarp, which provided much-needed shade, and set up some bright lights so Ochs and Taylor could paint through the night into the next day.

Ochs says they chose a very simple, high-contrast color scheme for the buildings, using specially made paint loaded with white pigment and a dark chocolate instead of a black. “We wanted it to be monochromatic as another way of bringing unity to all the different buildings,” he says. They employed a technique called “chiaroscuro,” which entails dramatics contrasts between lights and darks.

They also mottled the two paints together to get various light and dark shades. When they finished painting the buildings, they floated metallics over the top of the whole thing, a technique called “underpainting and glazing.”

“Since the final layers of color were going to be metallic gold and copper, we knew the whites and blacks had to be bold, because they would eventually be toned down under the layers of metallic pigment,” Ochs explains.

“If we had added any lights or darks to the gold or copper, they would have become muddy and lost their shine,” he continues. “The top thin layer of metallic gives the illusion of dimension. And when the sun hits the painting just right, it flashes like a brand new penny.”

Racing against Fay

As predicted, Fay was barreling their way Aug. 17, with a deluge of rain and high humidity in tow. It was day three and time to seal. Ochs and Taylor chose to use Arizona Polymer Flooring’s two-component Polyurethane 250 as a primer. They topped off three coats of that with one coat of APF’s Polyurethane 100 (a two-component aliphatic polyurethane) with a texture of 40-grit-to 60-grit poly-resin sand.

“Between every layer, the wind blew, the clouds darkened and another band of rain forced us to grab our materials and run for cover,” Ochs remembers. At the onset of each shower, they were lucky the Poly 250 had just enough time to flash and develop a skin so they never had any issues with moisture.

“We would towel-dry the work and get ready for the next layer of sealer when it would flat pour again,” he says.

Ochs and Taylor rolled on the Poly 100, a high-performance sealer known to be extremely hard, and not surprisingly, it was still quite sticky a half hour later. It usually takes between 4 and 6 hours to be touchable and 24 hours to be ready for light foot traffic – time they didn’t have.

“The clouds opened up once more and it felt like we had been hit by a wave,” Ochs says. “My heart stopped as I stood there gazing downward trying to grasp the realization of a full-blown failure. While my mind was racing with all the logistics of the time and cost to repair, I reached down and touched the surface. To my surprise, it was no longer sticky.” By the grace of God, the coating had cured just enough to resist the outpouring from Fay.

Homeward bound

After a well-deserved night’s rest, the duo headed for Duval Street to buy souvenirs when they noticed there were no tourists anywhere. Instead, work crews were busy securing storefront windows, and news media were set up on every street corner.

“What are you doing here?” someone asked. That, Ochs says, is when they discovered a mandatory evacuation had been declared for the Keys 12 hours prior. One store stayed open long enough for him to buy T-shirts for his two sons so he didn’t have to return home empty-handed.

“Fay chased our rental car for nearly five hours all the way back to Ft. Lauderdale,” Ochs recalls, adding they didn’t even stop to fill the tank before turning in the car. “Our standby tickets were barely honored as we were given the last two seats on the plane.” Hours later, the airport was closed.

Fay made her way through Florida, across the Gulf and eventually even blew into Arkansas. But, Ochs says, “she left our mural and us unscathed thanks to quality products, great people and a lot of luck.”

www.publicartwalks.com

www.imagesinconcrete.com

www.saumag.edu

Project at a Glance

Project: Mural at entrance of Freeman Justice Center, Key West, Fla., Outside the entrance of the Freeman Justice Center in Key West, Fla.

Decorative concrete contractor: Steven Ochs, art professor at Southern Arkansas University in Magnolia and owner of Public Art Walks, and Gerald Taylor, owner of Images in Concrete, El Dorado, Ark.

Scope of project: From concept to completion, create a culturally significant concrete mural for the entryway of the new Monroe County courthouse.