Located in Pacific Palisades, Calif., near Los Angeles, the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa is billed as one of the most visited museums in the United States. Dedicated to the study of ancient culture, the museum features art from Greece, Rome and Etruria. After an extensive five-year renovation, the Getty Villa reopened its doors in 2006 to an estimated 1.3 million annual visitors.

The primary design focus of the renovation was to modernize the existing museum, which is a replica of a Roman villa buried in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. To meld with the museum’s aesthetic, the project’s architects, Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti of Machado and Silvetti Associates, Boston, Mass., blended the vision of an archeological excavation with the technological requirements of a modern building. Executive architect SPF Architects, of Los Angeles, and general contractor and decorative structural and vertical concrete subcontractor Morley Construction Co. executed this vision using a huge array of decorative concrete surfaces.

Earlier this year, decorative concrete at the site was recognized by the American Society of Concrete Contractors Decorative Concrete Council in its annual Awards announcement. The museum project won first place in Multiple Applications – Commercial and Vertical Applications categories.

While the architects for this project had specified the use of decorative concrete in the past, they had never worked with it on the extensive scale that this project necessitated. “The architects were tasked with challenges such the need for parking, increased visitors, and new visitor services such as an auditorium, cafe, bookstore and outdoor amphitheatre, to name a few,” explains Morley construction coordinator Bill Boehle. “Although the 60-some-acre site seemed large, the existing museum structure sat in a deep canyon, and there was very little flat adjacent ground.

“To accommodate all of the new programming required, it was obvious to the designers that they would have to do expensive earthwork and bury many of the structures into the hillsides. This meant retaining walls.”

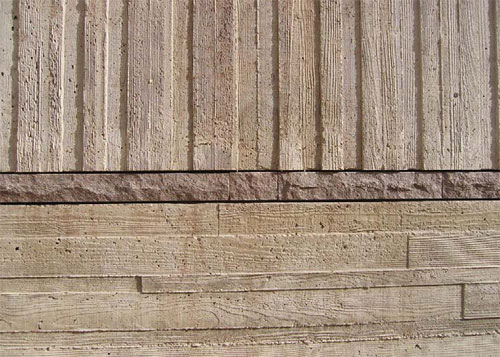

The new buildings are all concrete. And where exposed to public view, the walls are in fact decorative structural elements. “The decorative nature is gained by techniques such as using heavily sanded board forms that replicate deep wood grain or casting the walls with a mix that contains colored aggregates and exposing that aggregate by sandblasting or grinding,” says Boehle. “Other materials were introduced into the structural concrete by cladding or inserting into blockouts in the walls.”

The new structures needed to work with the Roman theme of the original museum. This idea inspired the Strata Wall. “The Strata Wall intimates or implies an archeological excavation where one encounters differing layers of earth and changing materials,” says Boehle. “The new design mimicked this naturally occurring stratum, and the buildings became a mixture of layers of wood, bronze, stone and concrete.”

An important design specification was that the strata elements needed to appear three-dimensional. Horizontal and vertical finishes needed to look the same – something that is difficult to achieve when placing concrete systematically. “Imagine a large block of concrete made of a homogeneous material, and we carved out stairs or other shapes,” Boehle explains. “The exposed surfaces of that block would look the same as if we carved it out of a block of granite. But in construction, we build in elements. We do walls first, then come back later and do horizontal surfaces. Each method is traditionally a different method of casting concrete, and to achieve the same look for vertical pours as well as horizontal ones was a situation that needed to be worked through.”

Additionally, the vertical elements were mostly functional retaining walls, which mandated different methods of pouring from the horizontal walking surfaces. The techniques were different for each application but the results needed to be similar. The team first brought the structural walls as close to the desired effect as possible and then matched nonstructural elements to the vertical walls.

“The structural aggregate in the mix needed to be both decorative, since it was to be exposed, and structural, because it needed to hold up the building,” Boehle says. “We searched for many months and did many trials to find suitable colored aggregates that met ASTM specs and were decorative enough for the designers.”

Once that was finished, they experimented with sandblasting, grinding, sandblasting, grinding, retarders and water-blasters to expose the aggregate. Eventually, all of the methods were used at various strata elevations, says Boehle.

The board-formed structural walls were a solution for creating a deep rustic wood-grain surface, but they provided their own challenges. The contractors mocked up multiple trial batches using various species of wood and different combinations of form release materials. Some wood species left a colored residue that was unacceptable, some wood could not accept the sandblasting, and some just did not do the job. Boehle explains that the sandblasted boards themselves were back-screwed to the plywood form and varied in length, height and thickness. “The forms needed to be sealed tight, the crews casting the walls had to place and consolidate the mix just right, and the forms had to be removed with extreme care,” he says. “Each wall was in essence a unique mold.”

Other than the finished retaining walls, all the horizontal surfaces are nonstructural topping slabs placed on structural subslabs. Where the strata called for exposed aggregate, the topping slabs were treated by broadcasting loose aggregate into wet, freshly placed slabs. Boehle says the aggregates were then tamped, cured and exposed via grinding and acid-washing.

Similar methods were used on vertical surfaces such as stair risers, except small batches of concrete packed with the colored aggregates were placed at the riser face to insure density uniformity. At horizontal locations where board-form was called for, premade wood forms were used to stamp the impression into the surface, and these in turned aligned with the veritcal board form pattern of the structural wall pours.

Precast concrete was used to replicate existing elements of the original museum. The desired finish involved was a delicate surface of fine-grain sand similar to a carved stone finish. “Our precaster would have no issue recreating this for decorative elements, but we needed this material and finish in large structural members such as beams and round Greek-looking columns 30 feet tall,” Boehle recalls. The precaster developed a molding procedure that allowed them to cast the round columns while minimizing joint or seam lines. A light sandblast on the surface gave them the desired finish.

Finally, some elements of the project lent themselves to using shotcrete. For certain nonstructural walls that needed an exposed aggregate finish, the contractors sprayed the wall form with a shotcrete mix packed with decorative aggregate. The aggregates were then exposed using retarders and water-and-acid washes. “Like with everything else,” says Boehle, “many months of trials were needed for all casting methods to get the right recipes.”

Project at a Glance

Client: J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa

Site size: 60 acres Project cost: $249 million (entire renovation)

Duration of project: 8 years (including several years of planning, budgeting, modeling and mock-ups)

Architects: Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti, Machado & Silvetti Associates, Boston, Mass. | www.machado-silvetti.com

Executive architect: SPF Architects, Los Angeles | www.spfa.com

Contractor: Morley Construction Co., Santa Monica, Calif. | www.morleybuilders.com

Subcontractors:

Morley Construction Co.: structural and decorative structural concrete | www.morleybuilders.com

Shaw and Sons Concrete Contractors, Costa Mesa, Calif.: decorative topping slabs | www.shawconstruction.com

Superior Gunite Construction, Lakeview Terrace, Calif.: decorative shotcrete | www.shotcrete.com

Willis Construction, San Juan Bautista, Calif.: precast elements | www.pre-cast.org

Awards: First place in the American Society of Concrete Contractors Decorative Concrete Council’s 2011 Awards in two categories: Vertical Applications – Over 1,500 Square Feet and Multiple Applications – Commercial – Over 1,500 Square Feet