I’m waiting for a plane in Vancouver, B.C. A flight to LAX. It’s Sunday and it’s been a great weekend! I arrived late Thursday night with my youngish uncle, Vito. We met frank and feisty Tom Ralston, of Tom Ralston Concrete, Santa Cruz, Calif., and the Australian mad scientist, Gary Jones, of Colormaker, Richmond, B.C., at The Sandbar Seafood Restaurant, snug under the Granville Island Bridge. We ate. We drank. We told the truth and lied, and then admitted that we had lied. We laughed. We talked business. We talked wives. We talked ex-wives. We cried, but just a little.

We added the charming and suave Englishman Paul Taylor at Rodney’s Oyster House (where he had overlaid the floor with Colormaker Pentimento, seeded it with crushed oyster shells, then ground) and subsequently shared Americanos and Cubans on the beach at English Bay. A real concretist “guys’ weekend,” but with no strippers … this trip. I guess we’re older now? Up to Callaghan Valley and Whistler, where we hiked, talked about rock, concrete and rock formations. Saturday night on Robson Street.

At Whistler, the landscapes were manicured, with homes and hotels gorgeous, and larger than life. Beams were of logs, much too large to have ever been handled by hand. Often, walls were a combination of fluid concrete and quarried stone. “Great weight” was a typical first impression. And these structures were begotten of stunning and difficult sites, also carved from stone. Granite domes, basalt columns, even crumbling slate scree – whether solid or not, they were all substantial, with their own gravity.

And today, Sunday, the culmination of our big concretist weekend, a dim sum brunch with Dave Burnham, husband of my business partner, Kelley. Burnham, of the Kiewit-Flatiron general partnership, gave us an exclusive and fascinating guided tour of the new Port Mann Bridge over the Fraser River. This is a big project. A massive project! Really outside the box. Complex engineering. Spendy (albeit still a good value) at a billion dollars plus. And Dave Burnham knows how big and massive it is. You see, he’s an equipment operator, and he’s run every crane on the project. He tells me that the steel and concrete in this bridge weigh somewhere between the weights of a really large lead brick and a black hole! And he’d know, ‘cause he and his cranes have lifted one helluva lot of it.

According to Dave, the cast-in-drilled-hole pilings of the Port Mann Bridge extend some 200-plus feet below the bottom of the river, through ancient alluvial deposits, through “schmoo” (extremely fine glacial till), and finally, landing on stable bedrock. That bedrock had better be stable, considering the reinforced concrete pylons it supports just some 600 feet above the pilings and the river. That’s a lot of mud and iron, and a lot of weight! The bridge looks heavy, and it is, but, aside from Dave and the other “Kiewit-Flatiron Boys,” none of us will ever “feel” it. That is, really feel it! We’ll see it. We’ll sense it. But we’ll have never actually understood what it means to heft this kind of weight, to have essentially borne it on our shoulders.

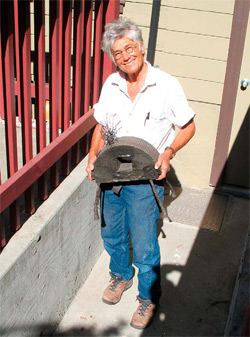

Macho “Big Bad Dave” Burnham and the “weight” of Kiewit-Flatiron’s Port Mann Bridge make me think of petite artist Grayson Malone and the gravity of her Cowboy Zen sculptures.

Grayson Malone has at least three things going for her, as far as I’m concerned. Now, these are superficial things, but I’m a superficial guy! She’s a smart and attractive chick. She’s a talented artist. And she works in concrete. I think these alone made her worth the attention. But there’s more.

I had discovered Grayson’s website, Cowboy-zen.com, while developing my own for the Southeast Asian market. My interest was piqued, so I checked it out. Really cool site! Smart commentary. Work photographed well. Hope I get a chance to see this stuff in person some day.

About a month back, Kathleen, our new neighbor and herself an ex-Berkeley artist, flagged me down and said, “Hey, Mike, I’ve just come from a craft festival. Do you know a woman named Grayson Malone? She also works in concrete.” Sounded familiar. I asked Kathleen what she thought about Grayson’s pieces. “They’re great,” she said. “Really well executed! Rich fine details.”

I also asked what their scale was. “The pieces are really small.” And this surprised me! I had surmised from the pictures on the site that the pieces would be quite large, like the size of furniture, or perhaps, decorative urns or really large planters. “No, they’re quite small. But, Mike, they’re really heavy. Like, really heavy!” Interesting. With Kathleen’s recommendation, I decided to contact Grayson and see if I could schedule a visit.

Grayson Malone, weight and scale Here’s Grayson Malone on the development of her metal-infused concrete pieces: “In my most recent work, I have integrated copper, bronze, steel, and iron (metals which have been ground into very fine particulates) directly into a portland cement matrix. The infusion of metal into cement differentiates my work from what is commonly expected from concrete, both visually and structurally. Not only does the concrete take on most of the characteristics of the specific metal used, it can also increase its compressive and tensile strengths.”

What metal and concrete have in common is synergistically amplified when they are combined in this way. Both are really heavy, and so are Malone’s pieces. What’s more, her pieces weren’t large. In fact, they were quite small, and this, in fact, emphasized their weight.

You see, when you look at a cast-in-place concrete structure like a ballpark or stadium, or a large piece of precast like the segments of the Port Mann Bridge, or even smaller elements like a staircase or a countertop, you can visualize the weight of the piece. It is sensed. However, this is a perception, not a physical experience.

For me, part of what makes Grayson’s pieces pure sensory concrete is their scale. You can actually heft them, and struggle with their weight. Exciting! It’s both an accessible and intimate experience. As a young guy, in my twenties, I used to have to hand-unload boxcar-loads of sacked cement that had shifted in Midwest “bumping yards.” Wow … this was quite a physical experience! However, I still think Grayson’s got it beat.

“Although I have created both functional and sculptural bodies of work, it has been most important to me that the object be able to stand alone with strict visual relativity and impact on any given space. I believe I have succeeded, by combining metals with concrete, in bringing into view an unusual medium dressed up in veritable simplicity.” Well said, Grayson! Sensory concrete: an unusual medium dressed up in veritable simplicity. Well said.

However, if I were to add something to this statement, it would be that her work expresses more than just visual relativity. There’s more to it than a mere expression of weight. Her infused-metal sculptures are physical and real. Tiny and dense, they are the actual embodiment of pure gravity.